In The Human Condition, Hannah Arendt describes human mortality as rectilinear. There is good reason for this: human life moves from birth to death through linear time, supposedly without circulating back to repeat the process and certainly not reversing direction. But this schematic of a straight line between life and death is out of place within Arendt’s recurrent theme of cyclicality. Circular movement is even present in her most obstinate category of human activity, work, which produces the durable, reified and (almost) immortal world of human artifice. This world stands apart from the earthfor Arendt and is the “non-mortal home for mortal beings” (Arendt 168).[1] The world, so called, is the realm of culture, composed of material severed from nature and earth. The world’s separation from earth constitutes mortality’s independence as a straight line. Rather than cutting through nature’s cycle, I argue that Arendt’s conception of mortality has a curvilinear trajectory that orbits the ring of nature in its decline, its decay, which is better suited to our modern, non-Euclidean, Archimedean point of perspective. The consequence of this argument is an acceleration of Arendt’s claim that the modern condition has become divorced from its groundedness and is, or at least was, increasingly threatened by the possibility that humans may leave behind the ground, the earth, nature and its givens for space travel. Rather than humans distancing themselves from their nature, I argue that the space between nature and culture is already enough to put us not at an increasing distance from nature but a constant remove much like an orbit. In short, it is the horizon that now retreats from us, curving down, seemingly upon itself, as this mortal coil falls after it.

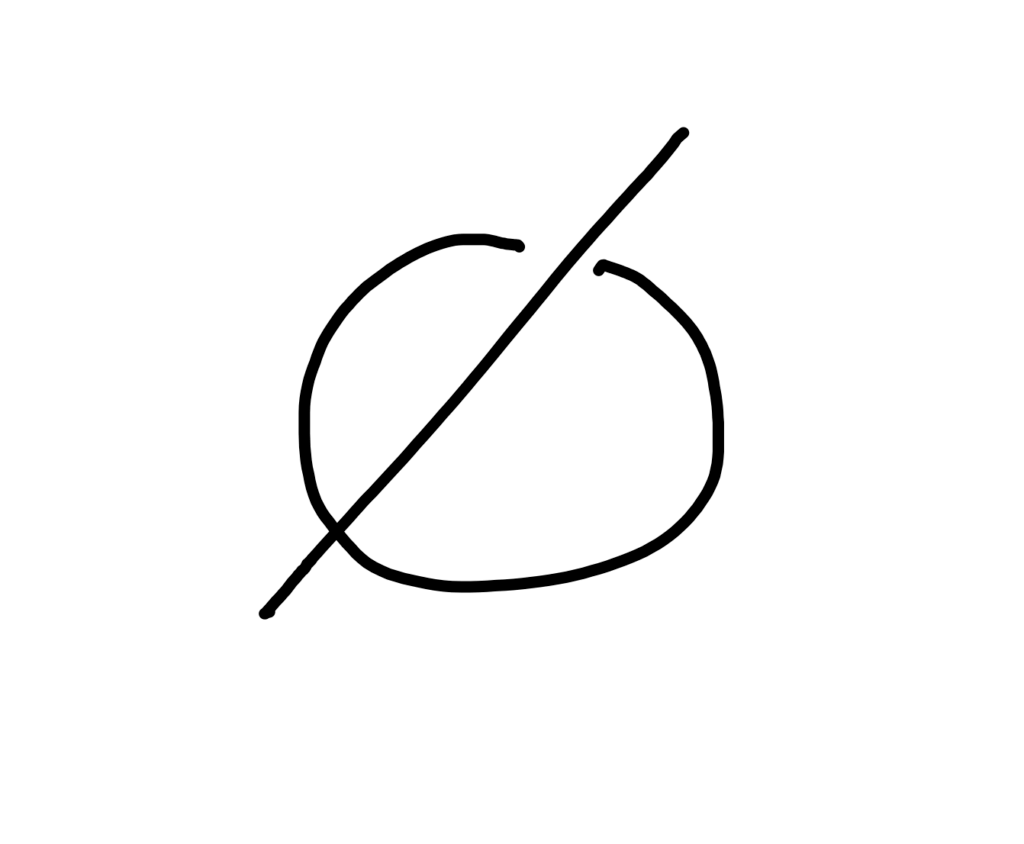

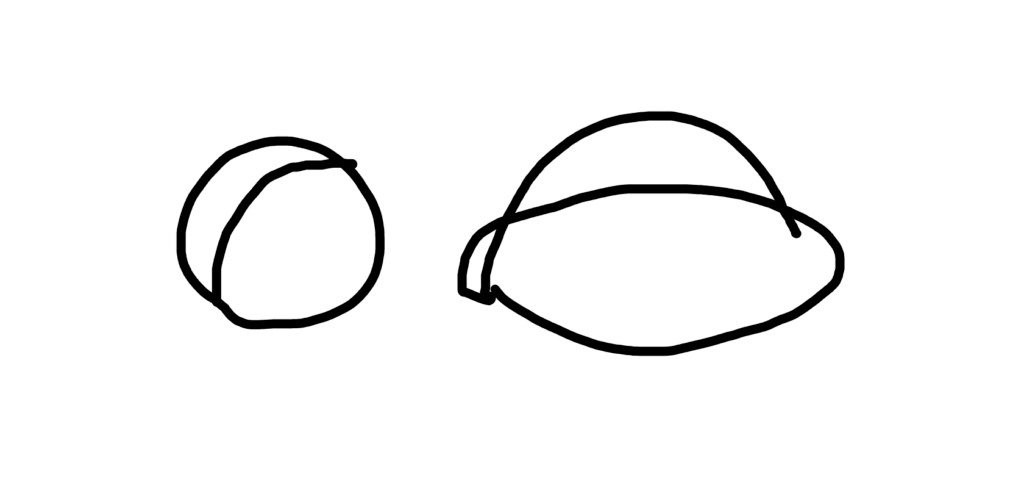

Both the world and the earth orbit. Arendt’s conception of rectilinear mortality obscures this fact. Nature, contained within the realm of earth, is found in the ceaseless turn-over of production and consumption. Fruit grows, is eaten, and the seeds are deposited elsewhere to begin a new plant that grows fruit: the circle of life. On its own, the movement of nature makes it difficult for humans to contemplate the eternal stillness of truth. As Arendt describes it, “Truth, be it the ancient truth of Being or the Christian truth of the living God, can reveal itself only in complete human stillness” (Arendt 15).[2] In modernity, however, truth has slipped into fact. Modernity’s increasing use of scientific methods to attain facts and gather incrementally more knowledge approaches truth, but never attains it, at least not in the way of an “ancient truth of Being.” Such a modern way of gathering facts emphasizes movement and an orbital, scientific activity that can only hope to test truth through “more doing,” never coming to an end, that is, never reaching the point it orbits (Arendt 290).[3] In contemporary terms, the stillness of truth can be thought of as a misinterpretation. We are not still. We are in free fall.[4] Orbit is effectively the speed of free fall coinciding with (the) curvature (of the earth) so that the horizon disappears beneath us. From this perspective, the objects we share an orbit with appear relatively still.

Being in space, such as you are when in orbit, is important context for Arendt’s notion of the human condition. Arendt begins The Human Condition by considering “the most radical change in the human condition we can imagine,” which “would be an emigration of men from the earth to some other planet” (Arendt 10).[5] Though there is no desire here to disagree with this claim per se, it is perplexing as to why Arendt supports her claim with the idea that leaving earth also means leaving behind human nature. Poetically speaking, yes, space-faring humans will have literally left behind what is typically called nature (earth), but they will also carry it with them in the material fabric of their being: their bodies. In addition to this, perhaps small, qualm is—what might be—an idiosyncratic assumption: wrapped up in modernity is the dissolution of a cosmological and theological firmament, the consequent infinity of the universe, the displacement of the human as its center or any center at all, and, finally, our bodily access to this expanded landscape, so to speak, with new and wholly alien horizons. Here, it seems there is a shifting identification with nature as unbound from the earth, instead pairing more with physical qualities in general. Now that outer space is physically accessible to humans and clearly the earth is part of a larger cosmos, “outer” space seems existent in a thoroughly natural sense. With this in mind, Arendt’s claim that space travel jeopardizes human nature seems overblown—however much we feel at the same time this to be deeply true—especially since the changes to human access to nature appear to have been undertaken in the wake of Galileo’s telescope and Cartesian doubt, which inserted instruments in between our sensory experience and grasp on reality. Perhaps the rectilinear conception of mortality that cuts away from the circular processes of earthly life bears some hidden insight into Arendt’s concern.

First, let us do away with the notion that mortality can be depicted as a straight line. For mortality to exist independently of natural death we need action, for it is action in Arendt’s theory of the vita activa that would give birth to the necessary independence of a self full of all the unforeseeable ramifications of the self and self-awareness. Action, as it plays out in public amongst the plurality of human wills, is cast by speech, in a broad sense, as a story. No story worthy of the name (or, rather, no story worthy of the who that constitutes the very essence of a story) can possibly tell of a life that unfurled in a straight line, since the very actions undertaken by our hero are both decisive, forking from other possible futures, as well as interactive with the bustle of other distinct human stories, each of which bearing its own trajectory, no less the intentions of the storyteller that reifies a hero’s actions after death. This reading of mortality adds effect to actual mortal life and affect to its story. In contrast, Arendt’s exclusively temporal consideration lacks the action that pulls mortal life from its natural circuit of life and death.

Arendt’s depiction of mortality is sensible. She uses rectilinear human mortality to starkly contrast the natural life cycles of everything else. She writes,

The mortality of men lies in the fact that individual life, with a recognizable life-story from birth to death, rises out of biological life. This individual life is distinguished from all other things by the rectilinear course of its movement, which, so to speak, cuts through the circular movement of biological life. This is mortality: to move along a rectilinear line in a universe where everything, if it moves at all, moves in a cyclical order.[6] (19)

In the first sentence we see that mortality, though bound to a life-story, is at base defined biologically. However, left out of this passage is that the very notion of growth and decay, the rise and fall of a life in a linear rather than cyclical fashion, is an overlay of the human world upon nature, which would appear as “a heap of unrelated articles, a non-world” (Arendt 9),[7] if an independent life were not bracketed from the rest of existence.[8] In this way, it is a life’s story, told by humans to themselves, that creates the rise and fall of mortal life. Without a story a life would fail to be understood as a rise and fall at all because it would be without the fixed orientation of a human perspective, instead revolving perpetually within the present moment.

Regardless of whether a mortal line runs crooked or straight, the usefulness of Arendt’s contrast between a finite human life and a continuous nature is clear. In the second line of the above passage Arendt suggests mortal life “cuts” through biology, as it is cut out. However, if we return to the first sentence, we see that mortality “rises out of biological life,” like a string loosened from a ball of yarn, emerging and submerging. Though the activity of human work stills the cycle of nature, even these durable interjections are only temporary as use and time will return everything to dust. Rather than cutting through life, then, mortality emerges from the cycle only to return to it, eventually. The mortal line is a gaze across the abyss of possibilities at the circle’s center to see the point at which our thread might submerge again.

In the third sentence we find that mortality does not reside within the context of the earth, but the universe. Our “everlasting” works and deeds raise a human life to a “divine nature” (Arendt 19).[9] Stories, for example, produce a superhuman awareness of our inescapable death. The straight line of mortality, then, is akin to the sighting of a distant planetary body through Galileo’s telescope that, if we were to try to actually reach it, would require an arching bearing that accounts for the curvature of spacetime, among other obstacles. Thus, the sighting of an endpoint, be it a planet or death, is mediated by an instrument of foresight beyond our immediate, natural senses that cuts artificially across the swirling of nature and the broad universe. But this straight line is not mortality, instead it is intentionality or maybe fate.

Instruments of intentionality and foresight, such as memento mori and telescopes, are evidence of works and deeds that are caused by the aspirations of mortals to exceed the confines of a straight line. Like Machiavelli advises his prince,

“A prudent man must always follow in the footsteps of great men and imitate those who have been outstanding. If his own prowess fails to compare with theirs, at least it has an air of greatness about it. He must behave like those archers who, if they are skilful, when the target seems too distant, know the capabilities of their bow and aim a good deal higher than their objective, not in order to shoot so high but so that by aiming high they can reach the target.”[10] (The Prince 49).

Though Machiavelli speaks of achieving great and noble goals, there is an analogy to draw here between the archer and the mortal being. For if a mortal being did not aim “a good deal higher than their objective,” they would merely skitter across the surface of bare life and survival before sinking into the grave. This is not the mortal life that defines the human condition that Arendt intends to describe. Confining herself to rectilinear mortality causes Arendt to obscure the immortal character of mortal lives; they strive to overshoot their bounds but are nonetheless drawn back in by natural limits.

In conclusion, Arendt’s geometric description of mortality as rectilinear, confined to straight lines, misses the extra-dimensional aims of mortal greatness. For the human condition, lifted out of the mire of immediate nature, trapped within its instruments, can hardly be said to have been trapped within the earth’s cycles ever since Galileo put our heads in the sky. Rather, humans have been in orbit for centuries, if not longer, drawn to the solid ground by the weight of their mortality. But by taking this path, so high up, humans find themselves in constant free fall, characterized not by their desire to leave earth behind so much as by a horizon that now stubbornly peels away from them.

Works Cited

Arendt, Hannah. The Human Condition, Second Edition. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press, 1998.

Machiavelli, Niccolò. The Prince. Harmondsworth: Penguin Books, 1983.

[1] Hannah Arendt, The Human Condition, 2nd edition, (Chicago: The University of Chicago Press, 1998), 168.

[2] Ibid., 15.

[3] Ibid., 290.

[4] This idea of being in free fall was inspired by Hito Steyerl’s text, “In Free Fall: A Thought Experiment on Vertical Perspective,” e-flux, vol. 24, 2011, https://www.e-flux.com/journal/24/67860/in-free-fall-a-thought-experiment-on-vertical-perspective/.

[5] Ibid., 10.

[6] Ibid., 19.

[7] Ibid., 9.

[8] “Only when they enter the man-made world can nature’s processes be characterized by growth and decay; only if we consider nature’s products, this tree or this dog, as individual things, thereby already removing them from their ‘natural’ surroundings and putting them into our world, do they begin to grow and to decay,” Ibid., 98.

[9] Ibid., 19.

[10] Niccolò Machiavelli, The Prince, trans. George Bull (Harmondsworth: Penguin Books, 1983), 49.