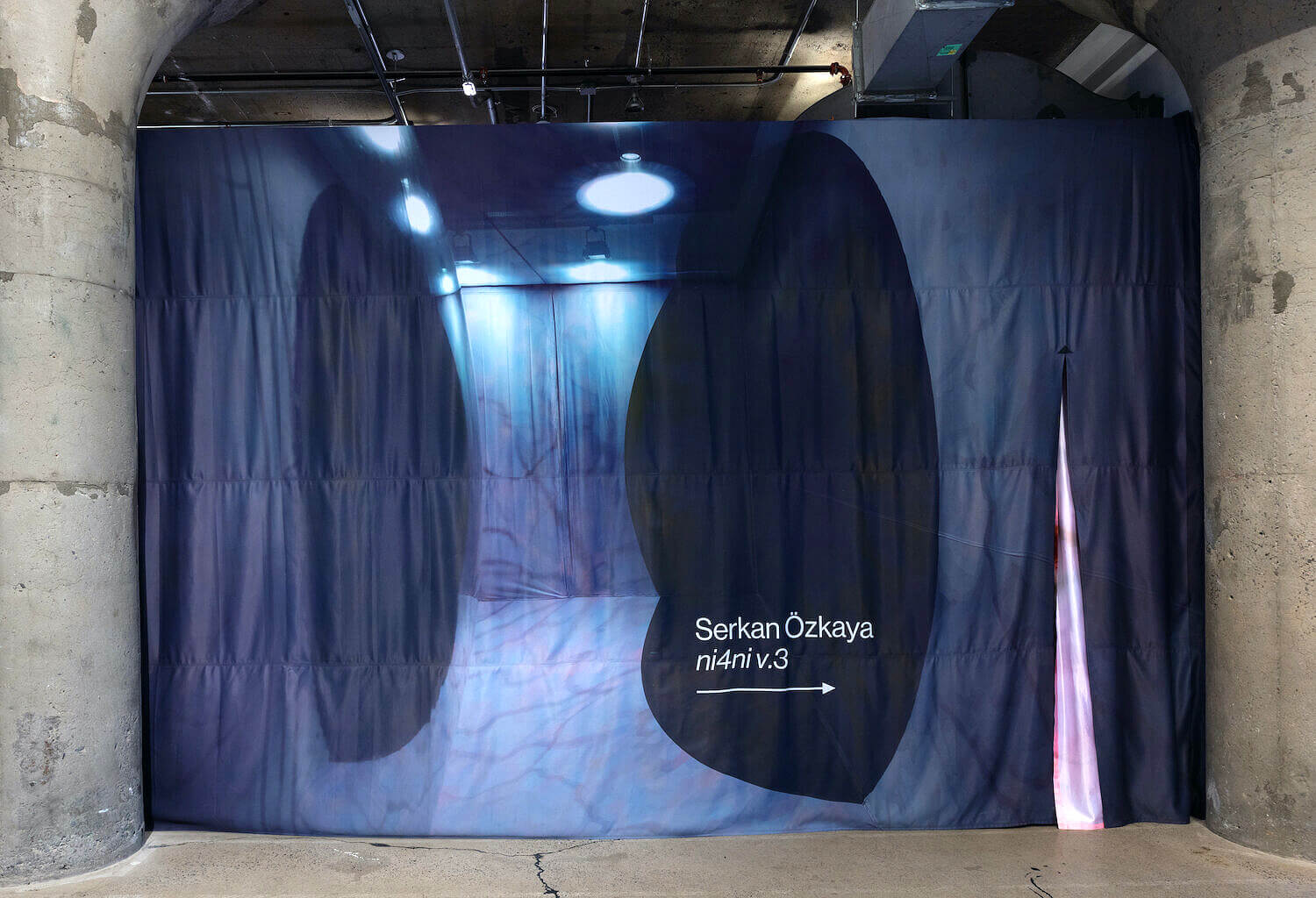

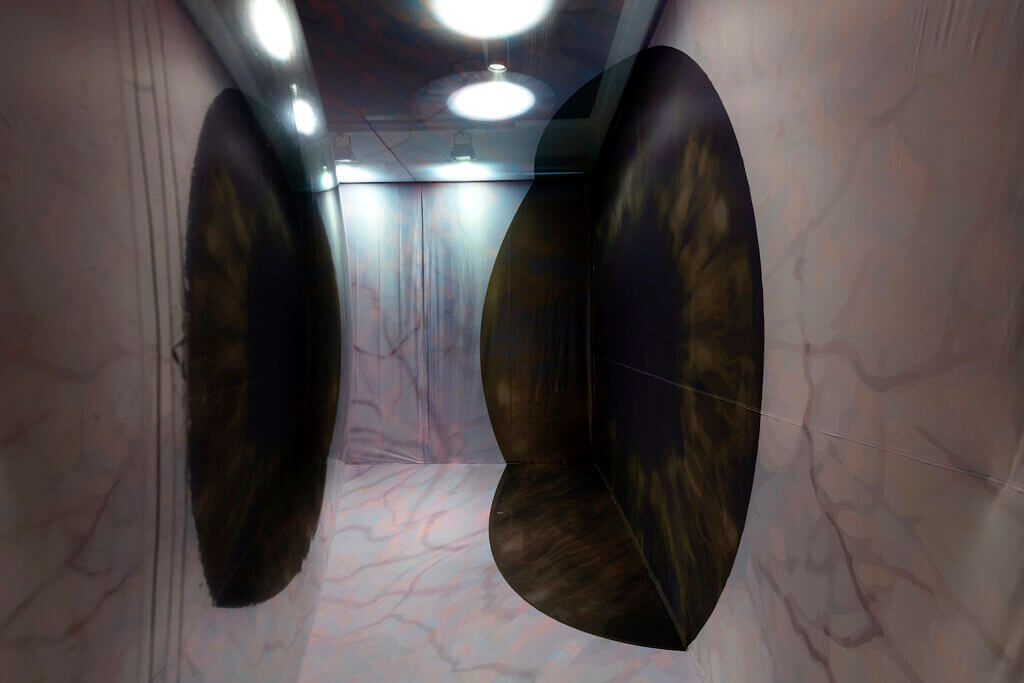

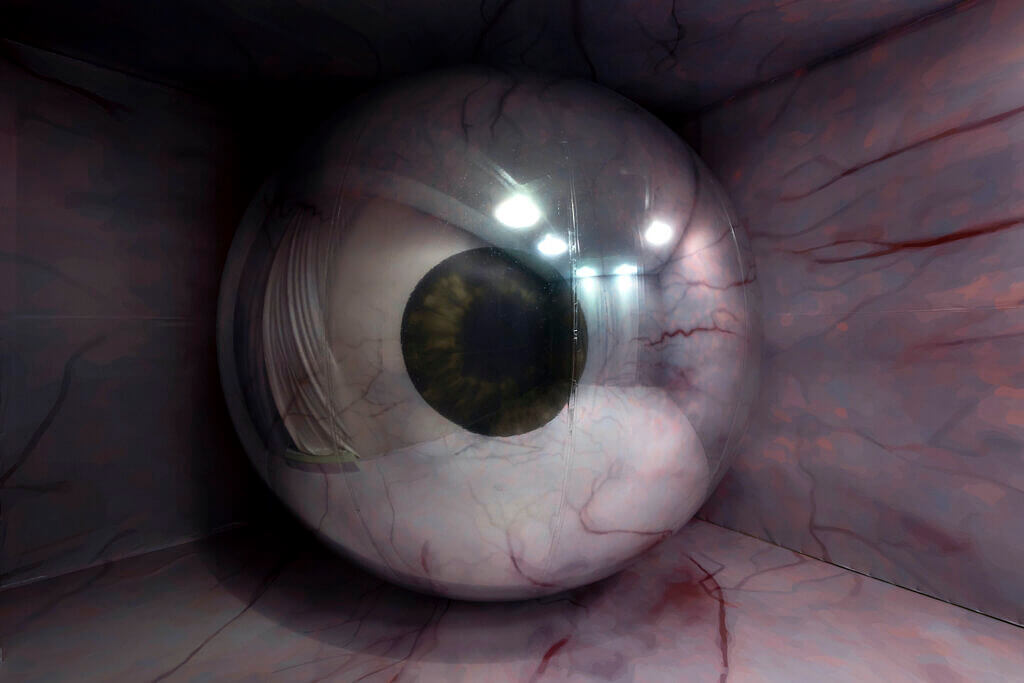

There is something suggestive about the slightly parted veil that cloaks Serkan Özkaya’s ni4ni. Heavy fabric separates the installation from the entrance foyer of the Museum of Contemporary Art (MOCA) in Toronto. Close to the bustle of the ticket booth and the nearby café, this small exhibition space has become its own self-contained gallery. Beyond its veil lies a fleshy interior. The walls and floor are masked with vinyl and fabric printed with blood vessels, an iris and pupil. Like being cradled against the inside of an eyelid, the relatively small space, soft wrinkles in the vinyl’s application and the transparent mesh stretched across the ceiling enhance a sense of membranes and taboo interstices. Inside this meaty pocket we are not alone. An enormous eye stares into itself, perhaps lost in thought or caught in a moment of dismemberment. However, the eye is not in fact there, but a reflection of the ensconcing, surrounding image cast across a chrome sphere. The (dead) stare is surprisingly close, so much so that we see ourselves in its orb-eyed envisioning. Greeted by our distorted reflection, and those of anyone else in the space, it appears as though we might, from the part in the veil, be emerging from four-dimensional folds hidden at the edge of an oversized cyclopean cornea.

Özkaya presents what appears to be a simple concept, yet it speaks to a complexity within contemporary experience that we found quite moving. At its most basic, ni4ni is an installation work composed of prints on fabric and vinyl and a large inflatable, reflective silver ball. The illusion of the eye, a directly observable experience, is made possible through a precisely calibrated distortion in the image splayed across the walls, ceiling and floor in order to appear correctly for viewers when looking at the ball / the eye. And this requires an attention to detail that is something we have come to expect in Özkaya’s practice, in which the artist pays close attention to elements that a viewer likely will not even notice but helps determine the experience he shares with us. The lighting, for example, is key to the staging of this scene. Due to the reflective nature of the chrome ball these lights are necessarily and precariously visible, making the balance between illusion and reality a careful one.

In ni4ni Özkaya plays with anamorphism, a mode of image creation that involves the manipulation of linear perspective to create an illusion that appears under highly specific conditions. A key historical example of this is the skull in Hans Holbein’s The Ambassadors (1533), which can only be seen in proper proportion from an extremely oblique view to the right side of the painting’s surface. It is not uncommon to use mirrors when creating anamorphic images, much like Özkaya has, especially curved or cylindrical mirrors that turn what might otherwise appear to be an abstract form into a coherent picture. ni4ni uses a large spherical mirror that generates an immersive anamorphic experience, one in which viewing the work means standing in the work, between its images, entangled with it – dancing. The viewer unavoidably exists under the weight and tumult of Özkaya’s gaze, or more properly that of his oversized cyclopean doppelgänger: it is the artist’s own umber eye that sees itself seeing.

MOCA’s exhibition of ni4ni is the third time this work has been manifest – hence “v.3” in the title – and each time the project adjusts to the dimensions and orientation of its new space. At Postmasters Gallery in New York City the installation was larger, as was the reflective sphere, providing an experience that we felt was quite contemplative. In this case we were both struck by the seeming lack of affect despite the fleshy quality of the eye, which appears not as a lively object but more like an amputation (for Maxwell) or as if the viewer is standing inside the eyeball (for Julian). At Galerist in Istanbul the space was smaller and more narrow, giving focus to the overall orientation, with the eye at one end looking off to the side. In this manifestation the eye looked more focused, distant but attentive to something beyond. At MOCA the work has more intimacy: we stand closer to the eye and have to negotiate our reflection more, as well as the bodies and reflections of other people in its orbit. This version of the installation feels more inquisitive, as if the eye asks questions of us and our relation to perception; there is a troubling of the human in this work that takes place at the level of presence and presentation. Özkaya’s title, ni4ni – an eye for an eye – hints at a competition between the actual eye of the viewer that sees the work and the image of the eye coalesced on the surface of the ball.

Reflecting on our experience of this work, we were reminded of the mysterious engraving in Camille Flammarion’s 1888 book L’atmosphère: météorologie Populaire that depicts a man crawling, pushing his way through the firmament to see the machinations of a universe turning. For Flammarion there seems to be a clarity to this divine realm, ordered in elemental layers, hidden just out of view beyond the infrathin boundary that separates it from the everyday. Beyond the veil of ni4ni, we do not find the other side of the firmament, but its metastable interior; we find a space in translation, a space of translation; we find a question about the existence of “self” in the contemporary world. A persistent problem of modernity, the “self” is understood not just as a conscious reflection on one’s identity, but also an infinite recursion – Duchamp would say a mirrorical return – of the thinness of this “me” that always seems to exist slightly beyond the bounds of perception. Özkaya toys with the limits of perception and human finitude but, unlike the old engraving, his work does not suggest a metaphysical “beyond.” Rather, ni4ni contains us in the tight ricochet of representation between what we see and what we think we see, between an image and its reflection.