1.

Form is the language of the world as it appears. From birth to death, from the moment we open our eyes until that when we close them, it is not a sea of sensible data with which we are not faced. Or, if this is technically the case, we still do not experience life as such. Rather, the world appears to us, from our very first moments, as formed.

2.

Even before speech we are immersed in a forest of forms, forms we may come to know in different ways but which nevertheless from the outset impress upon us their sense of being formed as a kind of simple truth. We might call this a ‘common sense’ view of form, where form appears not as itself as a question, but as that which in our common experience—common defined as everyday—comes before all questionability. While we may submit form to skepticism after the fact, its appearance is common in a second sense, as shared. This does not mean that we share in opinion, outlook, or understanding of form as it appears, but rather that we share in the simple fact of experiencing appearance in and as form. Form appears and appeals to us at the level of common sense.

3.

The formal analysis must no longer be taught as so many formal elements (line, shape, mass, etc.) cleaved from the formal unit in order to be analyzed, post-dissection, as separate from one another and from matter and meaning. No, formalism must aspire towards the dis-alienation of aesthetic form, analytically and philosophically. And since form is never separable in truth from meaning but only as a trick of logic and speech, the dis-alienation of form in the context of the formal analysis amounts to a radicalization of art historical pedagogy and practice that has for too long treated form and content as separate, and which must do so no more.

4.

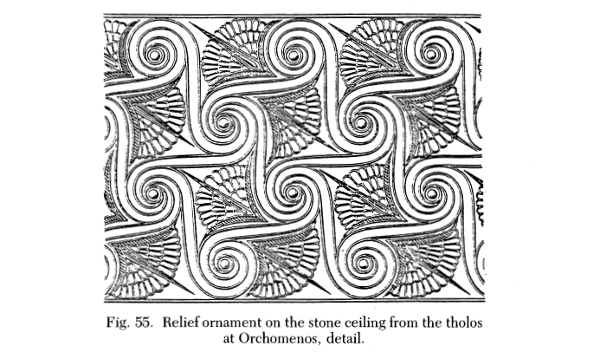

Ornament, from the Latin ornamentum, means equipment. From ornare, or to adorn. Ornament is the adornment of the structure with form—but in a non-frivolous sense, as equipment.

5.

Three metaphors for form, two that work and one that doesn’t: a tuning fork, a seismograph, a tree broken in a storm.

6.

With forms in nature there is an integral relationship between appearance as the formal ground and function as the activity of life, yet this relation does not render the world of non-human-made things formally determined. Rather, the world itself is intensely creative, even artistic, in so far as a central basis of real artistry is the firm connectability between the appearance and the actionability of form. The snake is the perfect metaphor and paradigmatic instantiation of this relationship, of the unity or immanence of function and form.

7.

When we use this word morphology, as in ‘morphology of art’, we take it to refer to the change of artistic forms through time. This is interesting, given that morph-ology literally means form-logic, nothing more nor nothing less. In biology, morphology refers to the study of the structural form of the organism, and in linguistics, morphology refers to the study of how words convey meaning. In each of these contexts, morphology requires the breaking of form (of the organism, or the word) down into the smallest of units, and then using these smallest of units in order to understand the greatest ones. That is, morphology in these contexts understands complexity as a real complex of smaller forms which, taken together, produce larger ones. Lest art history become co-opted by history proper, and the forms of art co-opted by historical ones, even the smallest formal unit must be taken to be always and at all times not only observable and analyzable within the (historical) development of art, but also within the formal one.

8.

Art historical truth must be not only sought within the realm of the image, but too in the terrain of form

9.

“As long as there have been men and they have lived, they have all felt this tragic ambiguity of their condition, but as long as there have been philosophers and they have thought, most of them have tried to mask it.”[1] This is as true for form as it is for human life; ambiguity is as constitutive of aesthetic form as it is of the lives we lead.

10.

The idea of art for its own sake is only an impoverished one if we take art in the first place to be poor in meaning.

[1] Simone de Beauvoir, The Ethics of Ambiguity (Paris: Éditions Gallimard, 1947), 6.